Sean Connery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

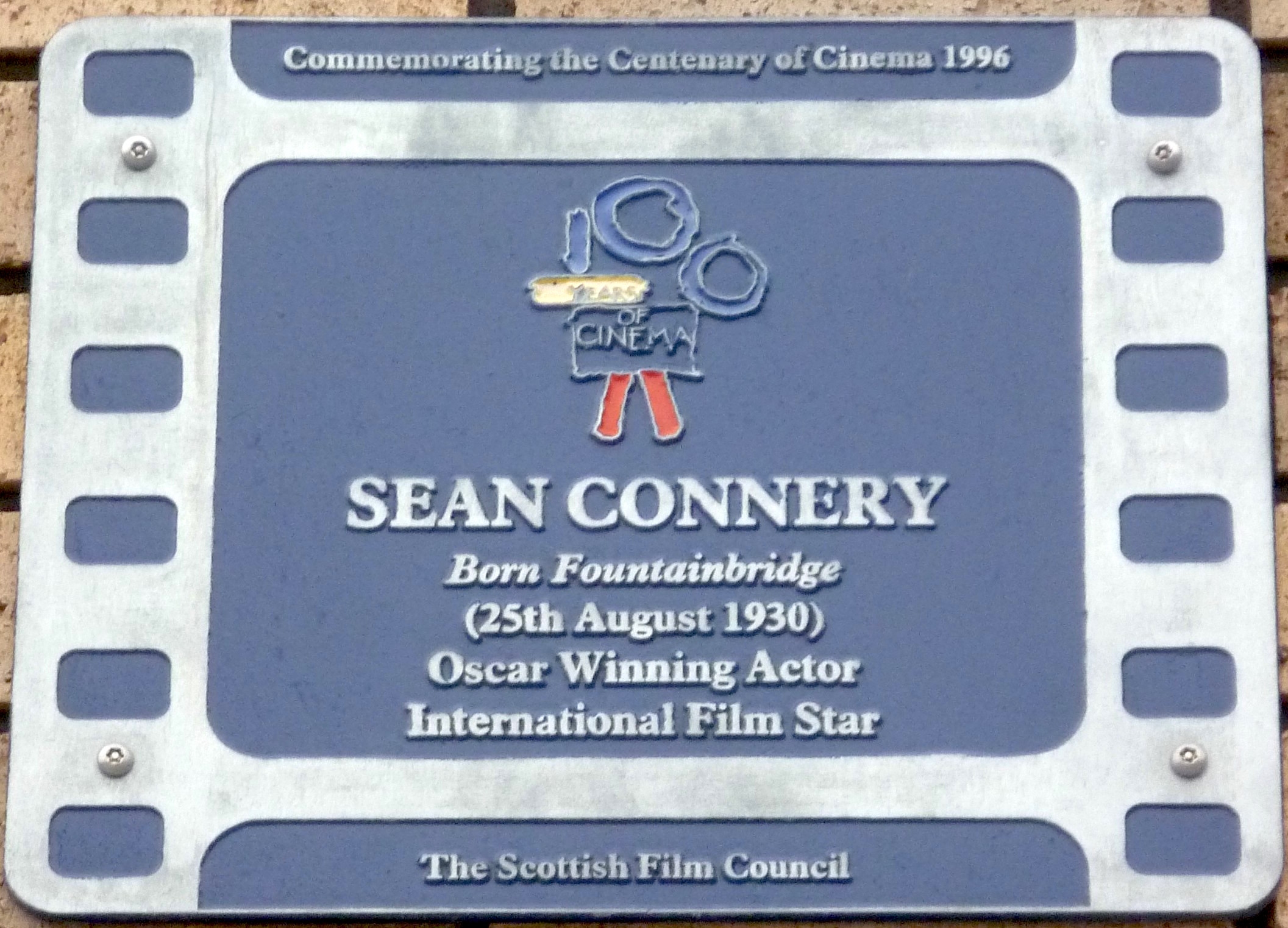

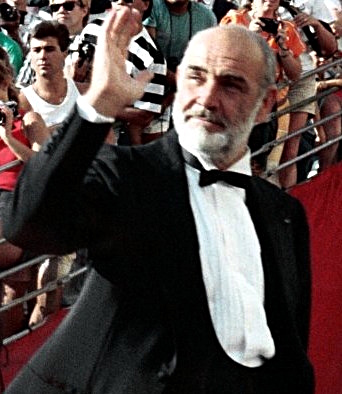

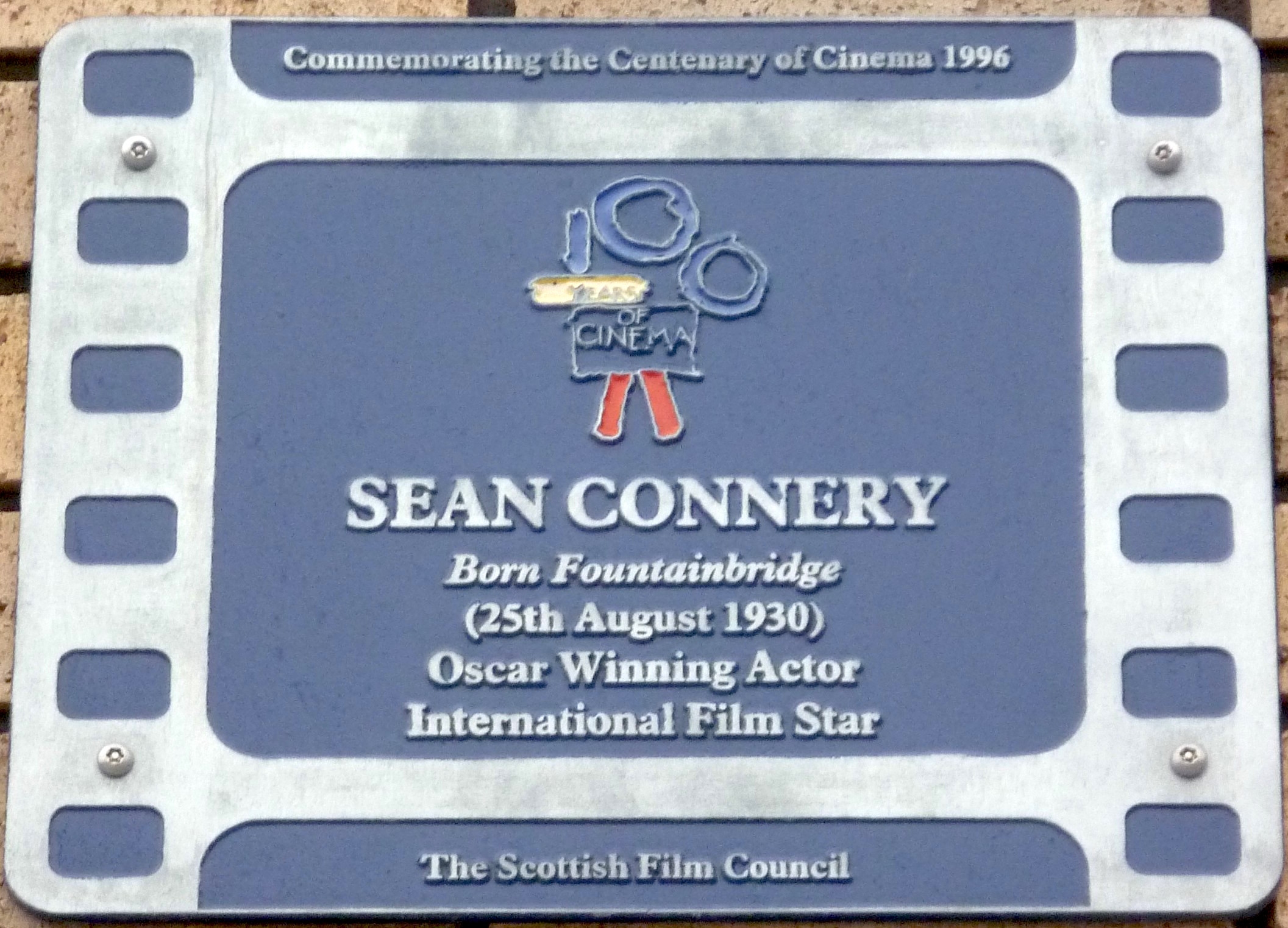

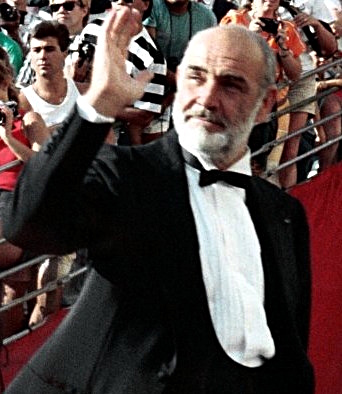

Sir Sean Connery (born Thomas Connery; 25 August 1930 – 31 October 2020) was a Scottish actor. He was the first actor to portray fictional British secret agent

Thomas Connery was born at the Royal Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 25 August 1930; he was named after his paternal grandfather. He was brought up at No. 176

Thomas Connery was born at the Royal Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 25 August 1930; he was named after his paternal grandfather. He was brought up at No. 176

In early 1957, Connery hired agent Richard Hatton who got him his first film role, as Spike, a minor

In early 1957, Connery hired agent Richard Hatton who got him his first film role, as Spike, a minor

Connery's breakthrough came in the role of British secret agent

Connery's breakthrough came in the role of British secret agent  Connery's portrayal of Bond owes much to stylistic tutelage from director

Connery's portrayal of Bond owes much to stylistic tutelage from director

Although Bond had made him a star, Connery grew tired of the role and the pressure the franchise put on him, saying " amfed up to here with the whole Bond bit" and "I have always hated that damned James Bond. I'd like to kill him".

Although Bond had made him a star, Connery grew tired of the role and the pressure the franchise put on him, saying " amfed up to here with the whole Bond bit" and "I have always hated that damned James Bond. I'd like to kill him".  Having played Bond six times, Connery's global popularity was such that he shared a Golden Globe Henrietta Award with Charles Bronson for "World Film FavoriteMale" in 1972. He appeared in

Having played Bond six times, Connery's global popularity was such that he shared a Golden Globe Henrietta Award with Charles Bronson for "World Film FavoriteMale" in 1972. He appeared in  Connery agreed to reprise Bond as an ageing agent 007 in '' Never Say Never Again'', released in October 1983. The title, contributed by his wife, refers to his earlier statement that he would "never again" return to the role. Although the film performed well at the box office, it was plagued with production problems: strife between the director and producer, financial problems, the Fleming estate trustees' attempts to halt the film, and Connery's wrist being broken by the fight choreographer,

Connery agreed to reprise Bond as an ageing agent 007 in '' Never Say Never Again'', released in October 1983. The title, contributed by his wife, refers to his earlier statement that he would "never again" return to the role. Although the film performed well at the box office, it was plagued with production problems: strife between the director and producer, financial problems, the Fleming estate trustees' attempts to halt the film, and Connery's wrist being broken by the fight choreographer,  Connery starred in

Connery starred in

When Connery received the American Film Institute's

When Connery received the American Film Institute's

During the production of ''South Pacific'' in the mid-1950s, Connery dated a Jewish "dark-haired beauty with a ballerina's figure", Carol Sopel, but was warned off by her family. He then dated Julie Hamilton, daughter of documentary filmmaker and

During the production of ''South Pacific'' in the mid-1950s, Connery dated a Jewish "dark-haired beauty with a ballerina's figure", Carol Sopel, but was warned off by her family. He then dated Julie Hamilton, daughter of documentary filmmaker and  Connery was married to French-Moroccan painter Micheline Roquebrune (born 4 April 1929) from 1975 until his death. The marriage survived a well-documented affair Connery had in the late 1980s with the singer and songwriter Lynsey de Paul, which she later regretted due to his views concerning domestic violence.

Connery owned the

Connery was married to French-Moroccan painter Micheline Roquebrune (born 4 April 1929) from 1975 until his death. The marriage survived a well-documented affair Connery had in the late 1980s with the singer and songwriter Lynsey de Paul, which she later regretted due to his views concerning domestic violence.

Connery owned the

Sean Connery

at the

James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

on film

On, on, or ON may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* On (band), a solo project of Ken Andrews

* On (EP), ''On'' (EP), a 1993 EP by Aphex Twin

* On (Echobelly album), ''On'' (Echobelly album), 1995

* On (Gary Glitter album), ''On'' (Gary Glit ...

, starring in seven Bond films between 1962 and 1983. Originating the role in '' Dr. No'', Connery played Bond in six of Eon Productions

Eon Productions Ltd. is a British film production company that primarily produces the ''James Bond'' film series. The company is based in London's Piccadilly and also operates from Pinewood Studios in the UK.

''Bond'' films

Eon was start ...

' entries and made his final appearance in '' Never Say Never Again''. Following his third appearance as Bond in '' Goldfinger'' (1964), in June 1965 ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine observed "James Bond has developed into the biggest mass-cult hero of the decade".

Connery began acting in smaller theatre and television productions until his breakout role as Bond. Although he did not enjoy the off-screen attention the role gave him, the success of the Bond films brought Connery offers from notable directors such as Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

, Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. He was nominated five times for the Academy Award: four for Best Director for ''12 Angry Men'' (1957), ''Dog Day Afternoon'' (1975), ''Network'' (1976), ...

and John Huston

John Marcellus Huston ( ; August 5, 1906 – August 28, 1987) was an American film director, screenwriter, actor and visual artist. He wrote the screenplays for most of the 37 feature films he directed, many of which are today considered ...

. Their films in which Connery appeared included ''Marnie

''Marnie'' is an English crime novel, written by Winston Graham and first published in 1961. It has been adapted as a film, a stage play and an opera.

Plot

''Marnie'' is about a young woman who makes a living by embezzling her employers' funds, ...

'' (1964), '' The Hill'' (1965), ''Murder on the Orient Express

''Murder on the Orient Express'' is a work of detective fiction by English writer Agatha Christie featuring the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 1 January 1934. In the U ...

'' (1974), and ''The Man Who Would Be King

"The Man Who Would Be King" (1888) is a story by Rudyard Kipling about two British adventurers in British India who become kings of Kafiristan, a remote part of Afghanistan. The story was first published in '' The Phantom Rickshaw and other E ...

'' (1975). He also appeared in '' A Bridge Too Far'' (1977), '' Highlander'' (1986), ''The Name of the Rose

''The Name of the Rose'' ( it, Il nome della rosa ) is the 1980 debut novel by Italian author Umberto Eco. It is a historical murder mystery set in an Italian monastery in the year 1327, and an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in ficti ...

'' (1986), ''The Untouchables

Untouchables or The Untouchables may refer to:

American history

* Untouchables (law enforcement), a 1930s American law enforcement unit led by Eliot Ness

* ''The Untouchables'' (book), an autobiography by Eliot Ness and Oscar Fraley

* ''The U ...

'' (1987), '' Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade'' (1989), ''The Hunt for Red October

''The Hunt for Red October'' is the debut novel by American author Tom Clancy, first published on October 1, 1984, by the Naval Institute Press. It depicts Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius as he seemingly goes rogue with his country's cutt ...

'' (1990), ''Dragonheart

''Dragonheart'' (stylized as ''DragonHeart'') is a 1996 fantasy adventure film directed by Rob Cohen and written by Charles Edward Pogue based on a story created by him and Patrick Read Johnson. The film stars Dennis Quaid, David Thewlis, ...

'' (1996), '' The Rock'' (1996), and ''Finding Forrester

''Finding Forrester'' is a 2000 American drama film written by Mike Rich and directed by Gus Van Sant. In the film, a black teenager, Jamal Wallace (Rob Brown (actor), Rob Brown), is invited to attend a prestigious private high school. By chance ...

'' (2000). Connery officially retired from acting in 2006, although he briefly returned for voice-over

Voice-over (also known as off-camera or off-stage commentary) is a production technique where a voice—that is not part of the narrative (non- diegetic)—is used in a radio, television production, filmmaking, theatre, or other presentation ...

roles in 2012.

His achievements in film were recognised with an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

, two BAFTA Awards

The British Academy Film Awards, more commonly known as the BAFTA Film Awards is an annual award show hosted by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to honour the best British and international contributions to film. The cere ...

(including the BAFTA Fellowship

The BAFTA Fellowship, or the Academy Fellowship, is a lifetime achievement award presented by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) in recognition of "outstanding achievement in the art forms of the moving image". The award is t ...

), and three Golden Globes

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

, including the Cecil B. DeMille Award

The Cecil B. DeMille Award is an honorary Golden Globe Award bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) for "outstanding contributions to the world of entertainment". The HFPA board of directors selects the honorees from a variet ...

and a Henrietta Award

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

. In 1987, he was made a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters

The ''Ordre des Arts et des Lettres'' (Order of Arts and Letters) is an order of France established on 2 May 1957 by the Minister of Culture. Its supplementary status to the was confirmed by President Charles de Gaulle in 1963. Its purpose is ...

in France, and he received the US Kennedy Center Honors lifetime achievement award in 1999. Connery was knighted in the 2000 New Year Honours for services to film drama.

Early life

Thomas Connery was born at the Royal Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 25 August 1930; he was named after his paternal grandfather. He was brought up at No. 176

Thomas Connery was born at the Royal Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 25 August 1930; he was named after his paternal grandfather. He was brought up at No. 176 Fountainbridge

Fountainbridge ( gd, Drochaid an Fhuarain) is an area of Edinburgh, Scotland, a short distance west of the city centre, adjoining Tollcross with East Fountainbridge and West Port to the east, Polwarth to the west and south, Dalry and Haymar ...

, a block which has since been demolished. His mother, Euphemia McBain "Effie" McLean, was a cleaning woman. She was born the daughter of Neil McLean and Helen Forbes Ross, and named after her father's mother, Euphemia McBain, wife of John McLean and daughter of William McBain from Ceres

Ceres most commonly refers to:

* Ceres (dwarf planet), the largest asteroid

* Ceres (mythology), the Roman goddess of agriculture

Ceres may also refer to:

Places

Brazil

* Ceres, Goiás, Brazil

* Ceres Microregion, in north-central Goiás ...

in Fife. Connery's father, Joseph Connery, was a factory worker and lorry driver.

Two of his paternal great-grandparents emigrated to Scotland from Wexford, Ireland in the mid-19th century, with his great-grandfather James Connery being an Irish Traveller

Irish Travellers ( ga, an lucht siúil, meaning "the walking people"), also known as Pavees or Mincéirs (Shelta: Mincéirí), are a traditionally peripatetic indigenous ethno-cultural group in Ireland.''Questioning Gypsy identity: ethnic na ...

. The remainder of his family was of Scottish descent, and his maternal great-grandparents were native Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

speakers from Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

and Uig on Skye. His father was a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, and his mother was a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. Connery had a younger brother Neil

Neil is a masculine name of Gaelic and Irish origin. The name is an anglicisation of the Irish ''Niall'' which is of disputed derivation. The Irish name may be derived from words meaning "cloud", "passionate", "victory", "honour" or "champion".. A ...

and was generally referred to in his youth as "Tommy". Although he was small in primary school, he grew rapidly around the age of 12, reaching his full adult height of at 18. Connery was known during his teen years as "Big Tam", and he said that he lost his virginity to an adult woman in an ATS uniform at the age of 14. He had an Irish childhood friend named Séamus; when the two were together, those who knew them both called Connery by his middle name Sean, emphasizing the alliteration of the two names. Since then Connery preferred to use his middle name.

Connery's first job was as a milkman in Edinburgh with St. Cuthbert's Co-operative Society. In 2009, Connery recalled a conversation in a taxi:

In 1946, at the age of 16, Connery joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, during which time he acquired two tattoos. Connery's official website says "unlike many tattoos, his were not frivolous – his tattoos reflect two of his lifelong commitments: his family and Scotland. ... One tattoo is a tribute to his parents and reads 'Mum and Dad', and the other is self-explanatory, 'Scotland Forever'". He trained in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

at the naval gunnery school and in an anti-aircraft crew. He was later assigned as an Able Seaman on HMS ''Formidable''. Connery was discharged

Discharge may refer to

Expel or let go

* Discharge, the act of firing a gun

* Discharge, or termination of employment, the end of an employee's duration with an employer

* Military discharge, the release of a member of the armed forces from serv ...

from the navy at the age of 19 on medical grounds because of a duodenal

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine ...

ulcer

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...

, a condition that affected most of the males in previous generations of his family.

Afterwards, he returned to the co-op and worked as a lorry driver, a lifeguard at Portobello swimming baths, a labourer, an artist's model for the Edinburgh College of Art

Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) is one of eleven schools in the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Tracing its history back to 1760, it provides higher education in art and design, architecture, histor ...

, and after a suggestion by former Mr. Scotland Archie Brennan, as a coffin polisher, among other jobs. The modelling earned him 15 shillings an hour. Artist Richard Demarco

Richard Demarco CBE (born 9 July 1930 in Edinburgh) is a Scottish artist and promoter of the visual and performing arts.

Early life

He was born at 9 Grosvenor Street in Edinburgh on 9 July 1930 the son of Carmino Demarco and his wife Elizabet ...

, at the time a student who painted several early pictures of Connery, described him as "very straight, slightly shy, too, too beautiful for words, a virtual Adonis".

Connery began bodybuilding

Bodybuilding is the use of progressive resistance exercise to control and develop one's muscles (muscle building) by muscle hypertrophy for aesthetic purposes. It is distinct from similar activities such as powerlifting because it focuses ...

at the age of 18, and from 1951 trained heavily with Ellington, a former gym instructor in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

. While his official website states he was third in the 1950 Mr. Universe contest, most sources place him in the 1953 competition, either third in the Junior class or failing to place in the Tall Man classification. Connery said he was soon deterred from bodybuilding when he found that Americans frequently beat him in competitions because of sheer muscle size and, unlike Connery, refused to participate in athletic activity which could make them lose muscle mass.

Connery was a keen footballer

A football player or footballer is a sportsperson who plays one of the different types of football. The main types of football are association football, American football, Canadian football, Australian rules football, Gaelic football, rugby ...

, having played for Bonnyrigg Rose in his younger days. He was offered a trial with East Fife. While on tour with ''South Pacific'', Connery played in a football match against a local team that Matt Busby, manager of Manchester United, happened to be scouting. According to reports, Busby was impressed with his physical prowess and offered Connery a contract worth £25 a week () immediately after the game. Connery said he was tempted to accept, but he recalls, "I realised that a top-class footballer could be over the hill by the age of 30, and I was already 23. I decided to become an actor and it turned out to be one of my more intelligent moves".

Career

Early career

Seeking to supplement his income, Connery helped out backstage at the King's Theatre in late 1951. During a bodybuilding competition held in London in 1953, one of the competitors mentioned that auditions were being held for a production of '' South Pacific'', and Connery landed a small part as one of the Seabees chorus boys. By the time the production reached Edinburgh, he had been given the part of Marine Cpl. Hamilton Steeves and was understudying two of the juvenile leads, and his salary was raised from £12 to £14–10s a week. The production returned the following year, out of popular demand, and Connery was promoted to the featured role of Lieutenant Buzz Adams, whichLarry Hagman

Larry Martin Hagman (September 21, 1931 – November 23, 2012) was an American film and television actor, director, and producer, best known for playing ruthless oil baron J. R. Ewing in the 1978–1991 primetime television soap opera, ''Dal ...

had portrayed in the West End.

While in Edinburgh, Connery was targeted by the Valdor gang, one of the most violent in the city. He was first approached by them in a billiard hall

A billiard, pool or snooker hall (or parlour, room or club; sometimes compounded as poolhall, poolroom, etc.) is a place where people get together for playing cue sports such as pool, snooker or carom billiards. Such establishments commonly serv ...

where he prevented them from stealing his jacket and was later followed by six gang members to a 15-foot-high (4.6 m) balcony at the Palais de Danse. There, Connery singlehandedly launched an attack against the gang members, grabbing one by the throat and another by the biceps and cracking their heads together. From then on, he was treated with great respect by the gang and gained a reputation as a "hard man".

Connery first met Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine (born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite; 14 March 1933) is an English actor. Known for his distinctive Cockney accent, he has appeared in more than 160 films in a career spanning seven decades, and is considered a British film ico ...

at a party during the production of ''South Pacific'' in 1954, and the two later became close friends. During this production at the Opera House, Manchester

The Opera House in Quay Street, Manchester, England, is a 1,920-seater commercial touring theatre that plays host to touring musicals, ballet, concerts and a Christmas pantomime. It is a Grade II listed building. The Opera House is one of the ma ...

, over the Christmas period of 1954, Connery developed a serious interest in the theatre through American actor Robert Henderson who lent him copies of the Ibsen works ''Hedda Gabler

''Hedda Gabler'' () is a play written by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. The world premiere was staged on 31 January 1891 at the Residenztheater in Munich. Ibsen himself was in attendance, although he remained back-stage. The play has been ca ...

'', ''The Wild Duck

''The Wild Duck'' (original Norwegian title: ''Vildanden'') is an 1884 play by the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. It is considered the first modern masterpiece in the genre of tragicomedy. ''The Wild Duck'' and ''Rosmersholm'' are "often ...

'', and ''When We Dead Awaken

''When We Dead Awaken'' ( no, Når vi døde vågner) is the last play written by Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen. Published in December 1899, Ibsen wrote the play between February and November of that year. The first performance was at the Hayma ...

'', and later listed works by the likes of Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel '' In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous E ...

, Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

, Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

, Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Joyce, and Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

for him to digest. Henderson urged him to take elocution lessons and got him parts at the Maida Vale

Maida Vale ( ) is an affluent residential district consisting of the northern part of Paddington in West London, west of St John's Wood and south of Kilburn. It is also the name of its main road, on the continuous Edgware Road. Maida Vale is ...

Theatre in London. He had already begun a film career, having been an extra in Herbert Wilcox

Herbert Sydney Wilcox Order of the British Empire, CBE (19 April 1890 – 15 May 1977) was a British film producer and film director, director.

He was one of the most successful British filmmakers from the 1920s to the 1950s. He is best know ...

's 1954 musical '' Lilacs in the Spring'' alongside Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Olivia ...

and Anna Neagle

Dame Florence Marjorie Wilcox (''née'' Robertson; 20 October 1904 – 3 June 1986), known professionally as Anna Neagle, was an English stage and film actress, singer, and dancer.

She was a successful box-office draw in the British cinema ...

.

Although Connery had secured several roles as an extra, he was struggling to make ends meet and was forced to accept a part-time job as a babysitter for journalist Peter Noble and his actress wife Marianne

Marianne () has been the national personification of the French Republic since the French Revolution, as a personification of liberty, equality, fraternity and reason, as well as a portrayal of the Goddess of Liberty.

Marianne is displayed in ...

, which earned him 10 shillings a night. He met Hollywood actress Shelley Winters

Shelley Winters (born Shirley Schrift; August 18, 1920 – January 14, 2006) was an American actress whose career spanned seven decades. She appeared in numerous films. She won Academy Awards for ''The Diary of Anne Frank'' (1959) and ''A Patch o ...

one night at Noble's house, who described Connery as "one of the tallest and most charming and masculine Scotsmen" she'd ever seen, and later spent many evenings with the Connery brothers drinking beer. Around this time, Connery was residing at TV presenter Llew Gardner's house. Henderson landed Connery a role in a £6 a week Q Theatre

The Q Theatre was a British theatre located near Kew Bridge in Brentford, west London, which operated between 1924 and 1958. It was built on the site of the former Kew Bridge Studios.

The theatre, seating 490 in 25 rows with a central aisle, w ...

production of Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English writer known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving around fictiona ...

's ''Witness for the Prosecution

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

'', during which he met and became friends with fellow-Scot Ian Bannen

Ian Edmund Bannen (29 June 1928 – 3 November 1999) was a Scottish actor with a long career in film, on stage, and on television. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in '' The Flight of the Phoenix'' (1965), the first ...

. This role was followed by ''Point of Departure'' and ''A Witch in Time'' at Kew, a role as Pentheus opposite Yvonne Mitchell

Yvonne Mitchell (born Yvonne Frances Joseph; 7 July 1915 – 24 March 1979) was an English actress and author. After beginning her acting career in theatre, Mitchell progressed to films in the late 1940s. Her roles include Julia in the 1954 BBC ...

in ''The Bacchae

''The Bacchae'' (; grc-gre, Βάκχαι, ''Bakchai''; also known as ''The Bacchantes'' ) is an ancient Greek tragedy, written by the Athenian playwright Euripides during his final years in Macedonia, at the court of Archelaus I of Macedon. ...

'' at the Oxford Playhouse

Oxford Playhouse is a theatre designed by Edward Maufe and F.G.M. Chancellor. It is situated in Beaumont Street, Oxford, opposite the Ashmolean Museum.

History

The Playhouse was founded as ''The Red Barn'' at 12 Woodstock Road, North Oxfor ...

, and a role opposite Jill Bennett in Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier ...

's play ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According to historian Paul Avrich, the ...

''.

During his time at the Oxford Theatre, Connery won a brief part as a boxer in the TV series ''The Square Ring'', before being spotted by Canadian director Alvin Rakoff

Alvin Rakoff (born Abraham Rakoff; February 6, 1927) is a Canadian director of film, television and theatre productions. He has worked with actors including Laurence Olivier, Peter Sellers, Sean Connery, Judi Dench, Rex Harrison, Rod Steiger, Hen ...

, who gave him multiple roles in ''The Condemned'', shot on location in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

in Kent. In 1956, Connery appeared in the theatrical production of ''Epitaph'', and played a minor role as a hoodlum in the "Ladies of the Manor" episode of the BBC Television

BBC Television is a service of the BBC. The corporation has operated a public broadcast television service in the United Kingdom, under the terms of a royal charter, since 1927. It produced television programmes from its own studios from 193 ...

police series ''Dixon of Dock Green

''Dixon of Dock Green'' was a BBC police procedural television series about daily life at a fictional London police station, with the emphasis on petty crime, successfully controlled through common sense and human understanding. It ran from 19 ...

''. This was followed by small television parts in '' Sailor of Fortune'' and ''The Jack Benny Program

''The Jack Benny Program'', starring Jack Benny, is a radio-TV comedy series that ran for more than three decades and is generally regarded as a high-water mark in 20th century American comedy. He played one role throughout his radio and televis ...

'' (on a special episode filmed in Europe).

In early 1957, Connery hired agent Richard Hatton who got him his first film role, as Spike, a minor

In early 1957, Connery hired agent Richard Hatton who got him his first film role, as Spike, a minor gangster

A gangster is a criminal who is a member of a gang. Most gangs are considered to be part of organized crime. Gangsters are also called mobsters, a term derived from ''mob'' and the suffix '' -ster''. Gangs provide a level of organization and ...

with a speech impediment in Montgomery Tully

Montgomery Tully (6 May 190410 October 1988) was an Irish film director and writer.

Film career

Born in Dublin, Tully studied at the University of London, and originally entered the film industry as a director of documentaries. Later, Tully wo ...

's ''No Road Back

''No Road Back'' is a 1957 British crime film directed by Montgomery Tully.''No Road Back''

at the

'' alongside at the

Skip Homeier

George Vincent Homeier (October 5, 1930 – June 25, 2017), known professionally as Skip Homeier, was an American actor who started his career at the age of eleven and became a child star.

Career Child actor

Homeier was born in Chicago, Illino ...

, Paul Carpenter, Patricia Dainton

Patricia Dainton (born 12 April 1930) is a Scottish actress who appeared in a number of film and television roles between 1947 and 1961.

Early years

Dainton was born Margaret Bryden Pate, in Hamilton, Scotland, the daughter of film and stage ...

, and Norman Wooland

Norman Wooland (16 March 19053 April 1989) was an English character actor who appeared in many major films, including several Shakespearean adaptations.

Wooland was born in Düsseldorf, Germany to British parents. During the Second World War he ...

. In April 1957, Rakoffafter being disappointed by Jack Palance

Jack Palance ( ; born Volodymyr Palahniuk ( uk, Володимир Палагню́к); February 18, 1919 – November 10, 2006) was an American actor known for playing tough guys and villains. He was nominated for three Academy Awards, all fo ...

decided to give the young actor his first chance in a leading role, and cast Connery as Mountain McLintock in BBC Television's production of ''Requiem for a Heavyweight

"Requiem for a Heavyweight" is a teleplay written by Rod Serling and produced for the live television show ''Playhouse 90'' on 11 October 1956. Six years later, it was adapted as a 1962 feature film starring Anthony Quinn, Jackie Gleason, Mickey R ...

'', which also starred Warren Mitchell

Warren Mitchell (born Warren Misell; 14 January 1926 – 14 November 2015) was a British actor. He was a BAFTA TV Award winner and twice a Laurence Olivier Award winner.

In the 1950s, Mitchell appeared on the radio programmes ''Educatin ...

and Jacqueline Hill

Grace Jacqueline Hill (17 December 1929 – 18 February 1993)Obituary

cuttin ...

. He then played a rogue lorry driver, Johnny Yates, in cuttin ...

Cy Endfield

Cyril Raker Endfield (November 10, 1914 – April 16, 1995) was an American screenwriter, director, author, magician and inventor. Having been named as a Communist at a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing and subsequently blacklisted, ...

's '' Hell Drivers'' (1957) alongside Stanley Baker

Sir William Stanley Baker (28 February 192828 June 1976) was a Welsh actor and film producer. Known for his rugged appearance and intense, grounded screen persona, he was one of the top British male film stars of the late 1950s, and later a pro ...

, Herbert Lom

Herbert Charles Angelo Kuchačevič ze Schluderpacheru (11 September 1917 – 27 September 2012), known professionally as Herbert Lom (), was a Czech-British actor who moved to the United Kingdom in 1939. In a career lasting more than 60 ye ...

, Peggy Cummins, and Patrick McGoohan. Later in 1957, Connery appeared in Terence Young Terence or Terry Young may refer to:

*Terence Young (director) (1915–1994), British film director

* Terence Young (politician) (born 1952), Canadian Conservative Party politician

* Terence Young (writer), Canadian writer

* Terry Young (American p ...

's poorly received MGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 a ...

action picture '' Action of the Tiger'' opposite Van Johnson

Charles Van Dell Johnson (August 25, 1916 – December 12, 2008) was an American film, television, theatre and radio actor. He was a major star at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer during and after World War II.

Johnson was described as the embodiment o ...

, Martine Carol, Herbert Lom

Herbert Charles Angelo Kuchačevič ze Schluderpacheru (11 September 1917 – 27 September 2012), known professionally as Herbert Lom (), was a Czech-British actor who moved to the United Kingdom in 1939. In a career lasting more than 60 ye ...

, and Gustavo Rojo

Gustavo Rojo Pinto (5 September 1923 – 22 April 2017) was a Uruguayan-Mexican actor.

Life and career

Gustavo Rojo was born on 5 September 1923 on a German ship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. His mother was the prominent Spanish auth ...

; the film was shot on location in southern Spain. He also had a minor role in Gerald Thomas

Gerald Thomas (10 December 1920 – 9 November 1993) was an English film director, best known for the long-running ''Carry On'' series of British film comedies.

Biography

Born in Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire, England, Thomas was educated ...

's thriller ''Time Lock

A time lock (also timelock) is a part of a locking mechanism commonly found in bank vaults and other high-security containers. The time lock is a timer designed to prevent the opening of the safe or vault until it reaches the preset time, eve ...

'' (1957) as a welder, appearing alongside Robert Beatty

Robert Rutherford Beatty (19 October 1909 – 3 March 1992) was a Canadian actor who worked in film, television and radio for most of his career and was especially known in the UK.

Early years

Beatty was born in Hamilton, Ontario, Hamilton, O ...

, Lee Patterson

Lee Patterson (March 31, 1929 – February 14, 2007) was a Canadian film and television actor.

Life and career

Patterson was born in Vancouver, British Columbia, as Beverley Frank Atherly Patterson. He attended the Ontario College of Art and ...

, Betty McDowall

Betty McDowall (1924 – 1993) was an Australian stage, film and television actress. She was born in Sydney, New South Wales in 1924.

Her television appearances include episodes of ''Z-Cars'', ''The Saint'' and ''The Prisoner''.

On stage, sh ...

, and Vincent Winter

Vincent Winter (29 December 1947 – 2 November 1998) was a Scottish child film actor who, as an adult, continued to work in the film industry as a production manager and in other capacities.

Career

Winter was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, and ...

; this commenced filming on 1 December 1956 at Beaconsfield Studios

Beaconsfield Film Studios is a British television and film studio in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. The studios were operational as a production site for films in 1922, and continued producing films - and, later, TV shows - until the 1960s. B ...

.

Connery had a major role in the melodrama '' Another Time, Another Place'' (1958) as a British reporter named Mark Trevor, caught in a love affair opposite Lana Turner

Lana Turner ( ; born Julia Jean Turner; February 8, 1921June 29, 1995) was an American actress. Over the course of her nearly 50-year career, she achieved fame as both a pin-up model and a film actress, as well as for her highly publicized pe ...

and Barry Sullivan Barry Sullivan may refer to:

*Barry Sullivan (American actor) (1912–1994), US film and Broadway actor

*Barry Sullivan (stage actor) (1821–1891), Irish born stage actor active in Britain and Australia

*Barry Sullivan (lawyer), Chicago lawyer and ...

. During filming, Turner's possessive gangster boyfriend, Johnny Stompanato

John Stompanato Jr. (October 10, 1925 – April 4, 1958), was a United States Marine who became a bodyguard and enforcer for gangster Mickey Cohen and the Cohen crime family.

In the mid-1950s, he began an abusive relationship with actress ...

, who was visiting from Los Angeles, believed she was having an affair with Connery. Connery and Turner had attended West End shows and London restaurants together. Stompanato stormed onto the film set and pointed a gun at Connery, only to have Connery disarm him and knock him flat on his back. Stompanato was banned from the set. Two Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

detectives advised Stompanato to leave and escorted him to the airport, where he boarded a plane back to the United States. Connery later recounted that he had to lay low for a while after receiving threats from men linked to Stompanato's boss, Mickey Cohen

Meyer Harris "Mickey" Cohen (September 4, 1913 – July 29, 1976) was an American gangster, boxer and entrepreneur based in Los Angeles during the mid-20th century.

Early life

Mickey Cohen was born on September 4, 1913, in New York City to Je ...

.

In 1959, Connery landed a leading role in director Robert Stevenson Robert Stevenson may refer to:

* Robert Stevenson (actor and politician) (1915–1975), American actor and politician

* Robert Stevenson (civil engineer) (1772–1850), Scottish lighthouse engineer

* Robert Stevenson (director) (1905–1986), Engl ...

's Walt Disney Productions

The Walt Disney Company, commonly known as Disney (), is an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios complex in Burbank, California. Disney was originally founded on October 1 ...

film ''Darby O'Gill and the Little People

''Darby O'Gill and the Little People'' is a 1959 American fantasy adventure film produced by Walt Disney Productions, adapted from the ''Darby O'Gill'' stories of Herminie Templeton Kavanagh. Directed by Robert Stevenson and written by Lawrence ...

'' (1959) alongside Albert Sharpe, Janet Munro

Janet Munro (born Janet Neilson Horsburgh; 28 September 1934 – 6 December 1972) was a British actress. She won a Golden Globe Award for her performance in the film ''Darby O'Gill and the Little People'' (1959) and received a BAFTA Film Awar ...

, and Jimmy O'Dea

James Augustine O'Dea (26 April 1899 – 7 January 1965) was an Irish actor and comedian.

Life

Jimmy O'Dea was born at 11 Lower Bridge Street, Dublin, to James O'Dea, an ironmonger, and Martha O'Gorman, who kept a small toy shop. He was one ...

. The film is a tale about a wily Irishman and his battle of wits with leprechaun

A leprechaun ( ga, leipreachán/luchorpán) is a diminutive supernatural being in Irish folklore, classed by some as a type of solitary fairy. They are usually depicted as little bearded men, wearing a coat and hat, who partake in mischief. ...

s. Upon the film's initial release, A. H. Weiler of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' praised the cast (save Connery whom he described as "merely tall, dark, and handsome") and thought the film an "overpoweringly charming concoction of standard Gaelic tall stories, fantasy and romance". He also had prominent television roles in Rudolph Cartier

Rudolph Cartier (born Rudolph Kacser, renamed himself in Germany to Rudolph Katscher;

17 April 1904 – 7 June 1994) was an Austrian television director, filmmaker, screenwriter and producer who worked predominantly in British television, exc ...

's 1961 productions of '' Adventure Story'' and ''Anna Karenina

''Anna Karenina'' ( rus, «Анна Каренина», p=ˈanːə kɐˈrʲenʲɪnə) is a novel by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy, first published in book form in 1878. Widely considered to be one of the greatest works of literature ever writt ...

'' for BBC Television, the latter of which he co-starred with Claire Bloom

Patricia Claire Bloom (born 15 February 1931) is an English actress. She is known for leading roles in plays such as ''A Streetcar Named Desire,'' ''A Doll's House'', and '' Long Day's Journey into Night'', and has starred in nearly sixty film ...

. Also in 1961 he portrayed the title role

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

in a CBC television film adaptation of Shakespeare's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' with Australian actress Zoe Caldwell

Zoe Ada Caldwell, (14 September 1933 – 16 February 2020) was an Australian actress. She was a four-time Tony Award winner, winning Best Featured Actress in a Play for '' Slapstick Tragedy'' (1966), and Best Actress in a Play for '' The Pri ...

cast as Lady Macbeth.

James Bond: 1962–1971, 1983

Connery's breakthrough came in the role of British secret agent

Connery's breakthrough came in the role of British secret agent James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

. He was reluctant to commit to a film series, but understood that if the films succeeded, his career would greatly benefit. Between 1962 and 1967, Connery played 007 in '' Dr. No'', '' From Russia with Love'', '' Goldfinger'', '' Thunderball'', and '' You Only Live Twice'', the first five Bond films produced by Eon Productions

Eon Productions Ltd. is a British film production company that primarily produces the ''James Bond'' film series. The company is based in London's Piccadilly and also operates from Pinewood Studios in the UK.

''Bond'' films

Eon was start ...

. After departing from the role, Connery returned for the seventh film, '' Diamonds Are Forever'', in 1971. Connery made his final appearance as Bond in '' Never Say Never Again'', a 1983 remake of ''Thunderball'' produced by Jack Schwartzman's Taliafilm. All seven films were commercially successful. James Bond, as portrayed by Connery, was selected as the third-greatest hero in cinema history by the American Film Institute

The American Film Institute (AFI) is an American nonprofit film organization that educates filmmakers and honors the heritage of the motion picture arts in the United States. AFI is supported by private funding and public membership fees.

Leade ...

.

Connery's selection for the role of James Bond owed a lot to Dana Broccoli, wife of producer Albert "Cubby" Broccoli

Albert Romolo Broccoli ( ; April 5, 1909 – June 27, 1996), nicknamed "Cubby", was an American film producer who made more than 40 motion pictures throughout his career. Most of the films were made in the United Kingdom and often filmed at P ...

, who is reputed to have been instrumental in persuading her husband that Connery was the right man. James Bond's creator, Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer who is best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., a ...

, originally doubted Connery's casting, saying, "He's not what I envisioned of James Bond looks," and "I'm looking for Commander Bond and not an overgrown stunt-man", adding that Connery (muscular, 6'2", and a Scot) was unrefined. Fleming's girlfriend Blanche Blackwell

Blanche Blackwell (; 9 December 1912 – 8 August 2017) was a Jamaican heiress, mother of Chris Blackwell, and an inspirational muse to Ian Fleming and Noël Coward.

Early life

Blanche Lindo was born on 9 December 1912 in San José, Costa R ...

told him Connery had the requisite sexual charisma, and Fleming changed his mind after the successful ''Dr. No'' première. He was so impressed, he wrote Connery's heritage into the character. In his 1964 novel ''You Only Live Twice'', Fleming wrote that Bond's father was Scottish and from Glencoe in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

.

Connery's portrayal of Bond owes much to stylistic tutelage from director

Connery's portrayal of Bond owes much to stylistic tutelage from director Terence Young Terence or Terry Young may refer to:

*Terence Young (director) (1915–1994), British film director

* Terence Young (politician) (born 1952), Canadian Conservative Party politician

* Terence Young (writer), Canadian writer

* Terry Young (American p ...

, who helped polish him while using his physical grace and presence for the action. Lois Maxwell

Lois Ruth Maxwell (born Lois Ruth Hooker; 14 February 1927 – 29 September 2007) was a Canadian actress who portrayed Miss Moneypenny in the first fourteen Eon-produced ''James Bond'' films (1962–1985). She was the first actress to play the ...

, who played Miss Moneypenny

Miss Moneypenny, later assigned the first names of Eve or Jane, is a fictional character in the James Bond novels and films. She is secretary to M, who is Bond's superior officer and head of the British Secret Intelligence Service ( MI6).

Al ...

, related that "Terence took Sean under his wing. He took him to dinner, showed him how to walk, how to talk, even how to eat". The tutoring was successful; Connery received thousands of fan letters a week after ''Dr. No's'' opening, and he became a major sex symbol in film.

Following the release of the film ''Dr. No'' in 1962, the line "Bond ... James Bond", became a catch phrase

A catchphrase (alternatively spelled catch phrase) is a phrase or expression recognized by its repeated utterance. Such phrases often originate in popular culture and in the arts, and typically spread through word of mouth and a variety of mass ...

in the lexicon of Western popular culture. Film critic Peter Bradshaw

Peter Bradshaw (born 19 June 1962) is a British writer and film critic. He has been chief film critic at ''The Guardian'' since 1999, and is a contributing editor at ''Esquire''.

Early life and education

Bradshaw was educated at Haberdasher ...

writes, "It is the most famous self-introduction from any character in movie history. Three cool monosyllables, surname first, a little curtly, as befits a former naval commander. And then, as if in afterthought, the first name, followed by the surname again. Connery carried it off with icily disdainful style, in full evening dress with a cigarette hanging from his lips. The introduction was a kind of challenge, or seduction, invariably addressed to an enemy. In the early 60s, Connery's James Bond was about as dangerous and sexy as it got on screen".

During the filming of ''Thunderball'' in 1965, Connery's life was in danger in the sequence with the sharks in Emilio Largo

Emilio Largo is a fictional character and the main antagonist from the 1961 James Bond novel '' Thunderball''. He appears in the 1965 film adaptation, again as the main antagonist, with Italian actor Adolfo Celi filling the role. Largo is also th ...

's pool. He had been concerned about this threat when he read the script. Connery insisted that Ken Adam

Sir Kenneth Adam (born Klaus Hugo George Fritz Adam; 5 February 1921 – 10 March 2016) was a German-British movie production designer, best known for his set designs for the James Bond films of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as for ''Dr. Stran ...

build a special Plexiglas

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) belongs to a group of materials called engineering plastics. It is a transparent thermoplastic. PMMA is also known as acrylic, acrylic glass, as well as by the trade names and brands Crylux, Plexiglas, Acrylite ...

partition inside the pool, but this was not a fixed structure, and one of the sharks managed to pass through it. He had to abandon the pool immediately.

Beyond Bond

Although Bond had made him a star, Connery grew tired of the role and the pressure the franchise put on him, saying " amfed up to here with the whole Bond bit" and "I have always hated that damned James Bond. I'd like to kill him".

Although Bond had made him a star, Connery grew tired of the role and the pressure the franchise put on him, saying " amfed up to here with the whole Bond bit" and "I have always hated that damned James Bond. I'd like to kill him". Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine (born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite; 14 March 1933) is an English actor. Known for his distinctive Cockney accent, he has appeared in more than 160 films in a career spanning seven decades, and is considered a British film ico ...

said of the situation, "If you were his friend in these early days you didn't raise the subject of Bond. He was, and is, a much better actor than just playing James Bond, but he became synonymous with Bond. He'd be walking down the street and people would say, 'Look, there's James Bond'. That was particularly upsetting to him".

While making the Bond films, Connery also starred in other films such as Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

's ''Marnie

''Marnie'' is an English crime novel, written by Winston Graham and first published in 1961. It has been adapted as a film, a stage play and an opera.

Plot

''Marnie'' is about a young woman who makes a living by embezzling her employers' funds, ...

'' (1964) and Sidney Lumet

Sidney Arthur Lumet ( ; June 25, 1924 – April 9, 2011) was an American film director. He was nominated five times for the Academy Award: four for Best Director for ''12 Angry Men'' (1957), ''Dog Day Afternoon'' (1975), ''Network'' (1976), ...

's '' The Hill'' (1965), which film critic Peter Bradshaw regards as his two great non-Bond pictures from the 1960s. In ''Marnie'', Connery starred opposite Tippi Hedren

Nathalie Kay "Tippi" Hedren (born January 19, 1930) is an American actress, animal rights activist, and former fashion model.

A successful fashion model who appeared on the front covers of ''Life'' and '' Glamour'' magazines, among others, Hed ...

. Connery had said he wanted to work with Hitchcock, which Eon arranged through their contacts. Connery also shocked many people at the time by asking to see a script, something he did because he was worried about being typecast as a spy and he did not want to do a variation of ''North by Northwest

''North by Northwest'' is a 1959 American spy thriller film, produced and directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint and James Mason. The screenplay was by Ernest Lehman, who wanted to write "the Hitchcock picture ...

'' or '' Notorious''. When told by Hitchcock's agent that Cary Grant

Cary Grant (born Archibald Alec Leach; January 18, 1904November 29, 1986) was an English-American actor. He was known for his Mid-Atlantic accent, debonair demeanor, light-hearted approach to acting, and sense of comic timing. He was one o ...

had not asked to see even one of Hitchcock's scripts, Connery replied: "I'm not Cary Grant". Hitchcock and Connery got on well during filming, and Connery said he was happy with the film "with certain reservations". In ''The Hill'', Connery wanted to act in something that wasn't Bond related, and he used his leverage as a star to feature in it. While the film wasn't a financial success it was a critical one, debuting at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

winning Best Screenplay. The first of five films he made with Lumet, Connery considered him to be one of his favourite directors. The respect was mutual, with Lumet saying of Connery's performance in ''The Hill'', "The thing that was apparent to me – and to most directors – was how much talent and ability it takes to play that kind of character who is based on charm and magnetism. It's the equivalent of high comedy and he did it brilliantly."

In the mid-1960s, Connery played golf with Scottish industrialist Iain Maxwell Stewart

Sir Iain Maxwell Stewart (1916–1985) LLD (Strathclyde), BSc, MINA, MINE, MIMEch.E was a Scottish industrialist with a strong interest in modernising industrial relations.

Background

Stewart was a son of William Maxwell Stewart (1874–192 ...

, a connection which led to Connery directing and presenting the documentary film ''The Bowler and the Bunnet

''The Bowler and the Bunnet'' was a Scottish television documentary programme on STV (TV channel), STV, directed and presented by Sean Connery. It is the only film ever directed by Connery.

The documentary, filmed in black and white, was a crit ...

'' in 1967. The film described the Fairfield Experiment, a new approach to industrial relations carried out at the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company

The Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Limited was a Scottish shipbuilding company in the Govan area on the Clyde in Glasgow. Fairfields, as it is often known, was a major warship builder, turning out many vessels for the Royal Navy ...

, Glasgow, during the 1960s; the experiment was initiated by Stewart and supported by George Brown George Brown may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* George Loring Brown (1814–1889), American landscape painter

* George Douglas Brown (1869–1902), Scottish novelist

* George Williams Brown (1894–1963), Canadian historian and editor

* G ...

, the First Secretary in Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

's cabinet, in 1966. The company was facing closure, and Brown agreed to provide £1 million (£13.135 million; US$15.55 million in 2021 terms) to enable trade unions, the management and the shareholders to try out new ways of industrial management.

Having played Bond six times, Connery's global popularity was such that he shared a Golden Globe Henrietta Award with Charles Bronson for "World Film FavoriteMale" in 1972. He appeared in

Having played Bond six times, Connery's global popularity was such that he shared a Golden Globe Henrietta Award with Charles Bronson for "World Film FavoriteMale" in 1972. He appeared in John Huston

John Marcellus Huston ( ; August 5, 1906 – August 28, 1987) was an American film director, screenwriter, actor and visual artist. He wrote the screenplays for most of the 37 feature films he directed, many of which are today considered ...

's ''The Man Who Would Be King

"The Man Who Would Be King" (1888) is a story by Rudyard Kipling about two British adventurers in British India who become kings of Kafiristan, a remote part of Afghanistan. The story was first published in '' The Phantom Rickshaw and other E ...

'' (1975) opposite Michael Caine. Playing two former British soldiers who set themselves up as kings in Kafiristan

Kāfiristān, or Kāfirstān ( ps, کاپیرستان, prs, کافرستان), is a historical region that covered present-day Nuristan Province in Afghanistan and Chitral District of Pakistan. This historic region lies on, and mainly comprises ...

, both actors regarded it as their favourite film. The same year, he appeared in ''The Wind and the Lion

''The Wind and the Lion'' is a 1975 American epic adventure film written and directed by John Milius and starring Sean Connery, Candice Bergen, Brian Keith, and John Huston. Made in Panavision and Metrocolor and produced by Herb Jaffe and Phil ...

'' opposite Candice Bergen

Candice Patricia Bergen (born May 9, 1946) is an American actress. She won five Primetime Emmy Awards and two Golden Globe Awards for her portrayal of the title character on the CBS sitcom ''Murphy Brown'' (1988–1998, 2018). She is also kno ...

who played Eden Pedecaris (based on the real-life Perdicaris incident), and in 1976 played Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depic ...

in ''Robin and Marian

''Robin and Marian'' is a 1976 British-American romantic adventure film from Columbia Pictures, shot in Panavision and Technicolor, that was directed by Richard Lester and written by James Goldman after the legend of Robin Hood. The film stars Sea ...

'' opposite Audrey Hepburn, who played Maid Marian

Maid Marian is the heroine of the Robin Hood legend in English folklore, often taken to be his lover. She is not mentioned in the early, medieval versions of the legend, but was the subject of at least two plays by 1600. Her history and circums ...

. Film critic Roger Ebert

Roger Joseph Ebert (; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American film critic, film historian, journalist, screenwriter, and author. He was a film critic for the ''Chicago Sun-Times'' from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, Ebert beca ...

, who had praised the double act of Connery and Caine in ''The Man Who Would Be King'', praised Connery's chemistry with Hepburn, writing: "Connery and Hepburn seem to have arrived at a tacit understanding between themselves about their characters. They glow. They really do seem in love".

During the 1970s, Connery was part of ensemble casts in films such as ''Murder on the Orient Express

''Murder on the Orient Express'' is a work of detective fiction by English writer Agatha Christie featuring the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 1 January 1934. In the U ...

'' (1974) with Vanessa Redgrave

Dame Vanessa Redgrave (born 30 January 1937) is an English actress and activist. Throughout her career spanning over seven decades, Redgrave has garnered numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Television Award, tw ...

and John Gielgud

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the Briti ...

, and played a British Army general in Richard Attenborough's war film '' A Bridge Too Far'' (1977), co-starring Dirk Bogarde and Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

. In 1974, he starred in John Boorman's sci-fi thriller ''Zardoz

''Zardoz'' is a 1974 science fantasy film written, produced, and directed by John Boorman and starring Sean Connery and Charlotte Rampling. It depicts a post-apocalyptic world (which Boorman says, in the audio commentary, may or may not be mat ...

''. Often called one of the "weirdest and worst movies ever made" it featured Connery in a scarlet mankini

The sling swimsuit is a one-piece swimsuit which is supported by fabric at the neck. Sling swimsuits provide as little coverage (or as much exposure) as, or even less than, a bikini. Monokini types also exist. The sling swimsuit is also known by ...

a revealing costume which generated much controversy for its unBond-like appearance. Despite being panned by critics at the time, the film has developed a cult following since its release. In the audio commentary to the film, Boorman relates how Connery would write poetry in his free time, describing him as "a man of great depth and intelligence" and possessing the "most extraordinary memory". In 1981, Connery appeared in the film ''Time Bandits

''Time Bandits'' is a 1981 British fantasy adventure film co-written, produced, and directed by Terry Gilliam. It stars Sean Connery, John Cleese, Shelley Duvall, Ralph Richardson, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, Peter Vaug ...

'' as Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husb ...

. The casting choice derives from a joke Michael Palin

Sir Michael Edward Palin (; born 5 May 1943) is an English actor, comedian, writer, television presenter, and public speaker. He was a member of the Monty Python comedy group. Since 1980, he has made a number of travel documentaries.

Palin w ...

included in the script, which describes the character's removing his mask and being "Sean Conneryor someone of equal but cheaper stature". When shown the script, Connery was happy to play the supporting role. In 1981 he portrayed Marshal William T. O'Niel in the science fiction thriller '' Outland''. In 1982, Connery narrated '' G'olé!'', the official film of the 1982 FIFA World Cup

The 1982 FIFA World Cup was the 12th FIFA World Cup, a quadrennial Association football, football tournament for men's senior national teams, and was played in Spain between 13 June and 11 July 1982. The tournament was won by Italy national foo ...

. That same year, he was offered the role of Daddy Warbucks

Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks is a fictional character from the comic strip ''Little Orphan Annie''. He made his first appearance in the New York ''Daily News'' in the ''Annie'' strip on September 27, 1924. In the series he is said to be around 52 year ...

in ''Annie

Annie may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Annie (given name), a given name and a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Annie (actress) (born 1975), Indian actress

* Annie (singer) (born 1977), Norwegian singer

The ...

'', going as far as taking voice lessons for the John Huston musical before turning down the part.

Connery agreed to reprise Bond as an ageing agent 007 in '' Never Say Never Again'', released in October 1983. The title, contributed by his wife, refers to his earlier statement that he would "never again" return to the role. Although the film performed well at the box office, it was plagued with production problems: strife between the director and producer, financial problems, the Fleming estate trustees' attempts to halt the film, and Connery's wrist being broken by the fight choreographer,

Connery agreed to reprise Bond as an ageing agent 007 in '' Never Say Never Again'', released in October 1983. The title, contributed by his wife, refers to his earlier statement that he would "never again" return to the role. Although the film performed well at the box office, it was plagued with production problems: strife between the director and producer, financial problems, the Fleming estate trustees' attempts to halt the film, and Connery's wrist being broken by the fight choreographer, Steven Seagal

Steven Frederic Seagal (; born April 10, 1952) is an American actor, screenwriter and martial artist. A 7th-dan black belt in aikido, he began his adult life as a martial arts instructor in Japan and eventually ended up running his father-in-l ...

. As a result of his negative experiences during filming, Connery became unhappy with the major studios and did not make any films for two years. Following the successful European production ''The Name of the Rose

''The Name of the Rose'' ( it, Il nome della rosa ) is the 1980 debut novel by Italian author Umberto Eco. It is a historical murder mystery set in an Italian monastery in the year 1327, and an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in ficti ...

'' (1986), for which he won a BAFTA Award for Best Actor, Connery's interest in more commercial material was revived. That same year, a supporting role in '' Highlander'' showcased his ability to play older mentors to younger leads, which became a recurring role in many of his later films.

In 1987, Connery starred in Brian De Palma

Brian Russell De Palma (born September 11, 1940) is an American film director and screenwriter. With a career spanning over 50 years, he is best known for his work in the suspense, crime and psychological thriller genres. De Palma was a leading ...

's ''The Untouchables

Untouchables or The Untouchables may refer to:

American history

* Untouchables (law enforcement), a 1930s American law enforcement unit led by Eliot Ness

* ''The Untouchables'' (book), an autobiography by Eliot Ness and Oscar Fraley

* ''The U ...

'', where he played a hard-nosed Irish-American cop alongside Kevin Costner

Kevin Michael Costner (born January 18, 1955) is an American actor, producer, film director and musician. He has received various accolades, including two Academy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, and two Screen Actor ...

's Eliot Ness

Eliot Ness (April 19, 1903 – May 16, 1957) was an American Prohibition agent known for his efforts to bring down Al Capone and enforce Prohibition in Chicago. He was the leader of a team of law enforcement agents, nicknamed The Untouchables. ...

. The film also starred Charles Martin Smith

Charles Martin Smith (born October 30, 1953) is an American actor, writer, and director of film and television, based in British Columbia. He is known for his roles in ''American Graffiti'' (1973), ''The Buddy Holly Story'' (1978), '' Never Cry Wo ...

, Patricia Clarkson

Patricia Davies Clarkson (born December 29, 1959) is an American actress. She has starred in numerous leading and supporting roles in a variety of films ranging from independent film features to major film studio productions. Her accolades in ...

, Andy Garcia

Andy may refer to:

People

*Andy (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Horace Andy (born 1951), Jamaican roots reggae songwriter and singer born Horace Hinds

*Katja Andy (1907–2013), German-American pianist and piano ...

, and Robert De Niro as Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the ...

. The film was a critical and box-office success. Many critics praised Connery for his performance, including Roger Ebert, who wrote: "The best performance in the movie is Connery... ebrings a human element to his character; he seems to have had an existence apart from the legend of the Untouchables, and when he's onscreen we can believe, briefly, that the Prohibition Era

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic be ...

was inhabited by people, not caricatures". For his performance, Connery received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

Connery starred in

Connery starred in Steven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Spie ...

's '' Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade'' (1989), playing Henry Jones, Sr., the title character's father, and received BAFTA and Golden Globe Award nominations. Harrison Ford said Connery's contributions at the writing stage enhanced the film. "It was amazing for me in how far he got into the script and went after exploiting opportunities for character. His suggestions to George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

ucas

The Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS ) is a UK-based organisation whose main role is to operate the application process for British universities. It operates as an independent charity, funded by fees charged to applicants an ...

at the writing stage really gave the character and the picture a lot more complexity and value than it had in the original screenplay". His subsequent box-office hits included ''The Hunt for Red October

''The Hunt for Red October'' is the debut novel by American author Tom Clancy, first published on October 1, 1984, by the Naval Institute Press. It depicts Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius as he seemingly goes rogue with his country's cutt ...

'' (1990), ''The Russia House

''The Russia House'' is a spy novel by British writer John le Carré published in 1989. The title refers to the nickname given to the portion of the British Secret Intelligence Service that was devoted to spying on the Soviet Union. A film b ...

'' (1990), '' The Rock'' (1996), and '' Entrapment'' (1999). In 1996, he voiced the role of Draco the dragon in the film ''Dragonheart

''Dragonheart'' (stylized as ''DragonHeart'') is a 1996 fantasy adventure film directed by Rob Cohen and written by Charles Edward Pogue based on a story created by him and Patrick Read Johnson. The film stars Dennis Quaid, David Thewlis, ...

''. He also appeared in a brief cameo as King Richard the Lionheart

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was overl ...

at the end of '' Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves'' (1991). In 1998, Connery received the BAFTA Fellowship

The BAFTA Fellowship, or the Academy Fellowship, is a lifetime achievement award presented by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) in recognition of "outstanding achievement in the art forms of the moving image". The award is t ...

, a lifetime achievement award from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

.

Connery's later films included several box-office and critical disappointments such as ''First Knight

''First Knight'' is a 1995 medieval film based on Arthurian legend, directed by Jerry Zucker. It stars Sean Connery as King Arthur, Richard Gere as Lancelot, Julia Ormond as Guinevere and Ben Cross as Malagant.

The film follows the rogue La ...

'' (1995), '' Just Cause'' (1995), '' The Avengers'' (1998), and ''The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

''The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen'' (''LoEG'') is a comic book series (inspired by the 1960 British film ''The League of Gentlemen'') co-created by writer Alan Moore and artist Kevin O'Neill which began in 1999. The series spans four vol ...

'' (2003); however, he received positive reviews for his performance in ''Finding Forrester

''Finding Forrester'' is a 2000 American drama film written by Mike Rich and directed by Gus Van Sant. In the film, a black teenager, Jamal Wallace (Rob Brown (actor), Rob Brown), is invited to attend a prestigious private high school. By chance ...

'' (2000). He also received a Crystal Globe for outstanding artistic contribution to world cinema. In a 2003 UK poll conducted by Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned enterprise, state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a four ...